Since publishing my experimental analysis of managers yesterday, I’ve received some questions about luck and positions in the table. Earlier today I clarified the post to explain why, in a table fixed at twenty positions, it’s hard to be both very lucky and very good or very unlucky and very bad. I thought it would be worth showing what happened when I relaxed this constraint.

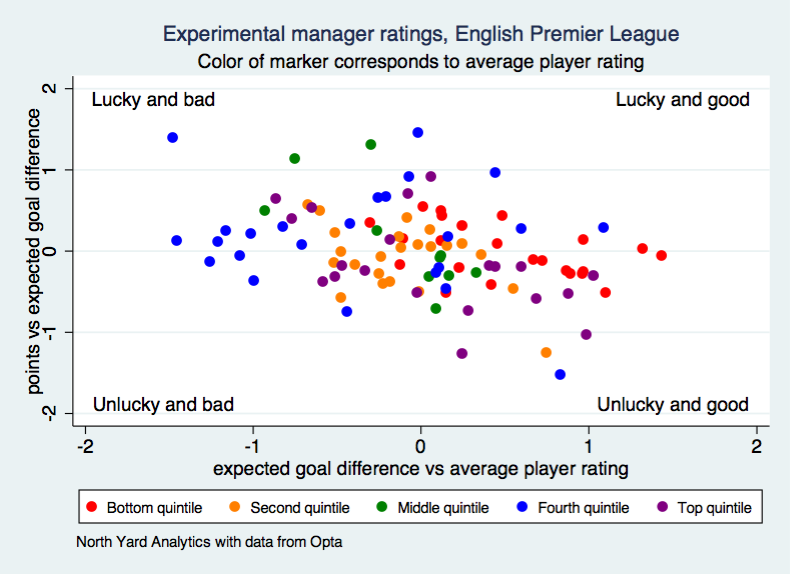

A club’s performance in terms of points isn’t quite as restricted, since few teams get close to the minimum (0) or maximum (114). Of course, going from points to positions in the table requires a bit of luck, too, since it’s dependent on other clubs’ results. But if we strip out that particular kind of luck, we can still look at the others in a more flexible setting. Here are all the graphs from yesterday’s post – plus the ones I posted on Twitter – this time with points instead of positions in the “luck” metric:

All clubs, all seasons 2010-11 through 2014-15:

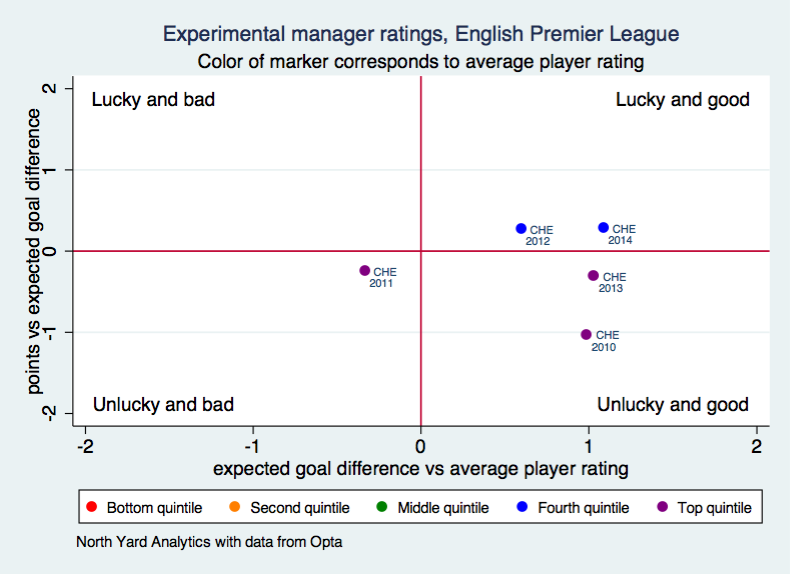

Chelsea: (unlucky Ancelotti!)

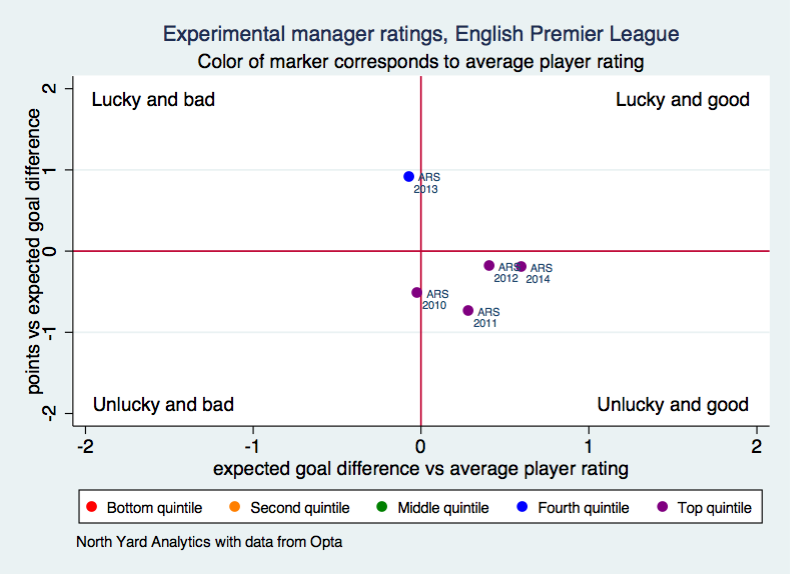

Arsenal: (lucky to overperform in 2013-14)

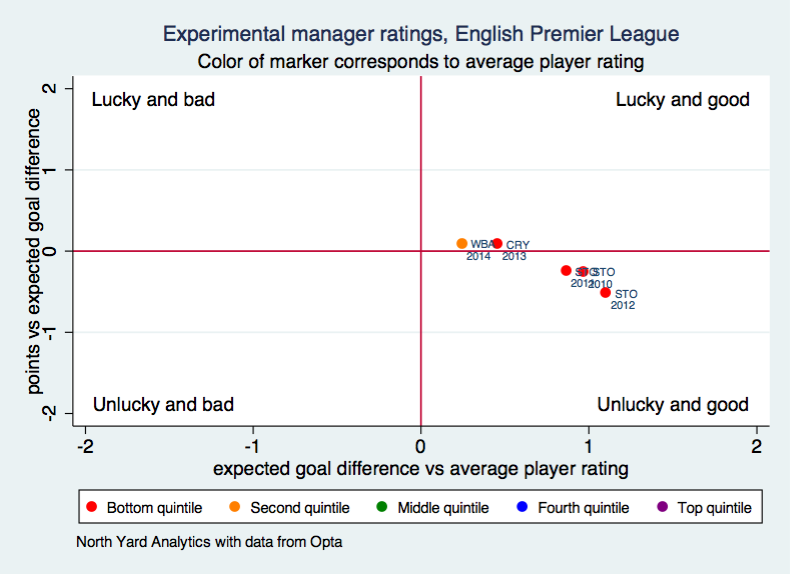

Tony Pulis: (good manager who can’t catch a break)

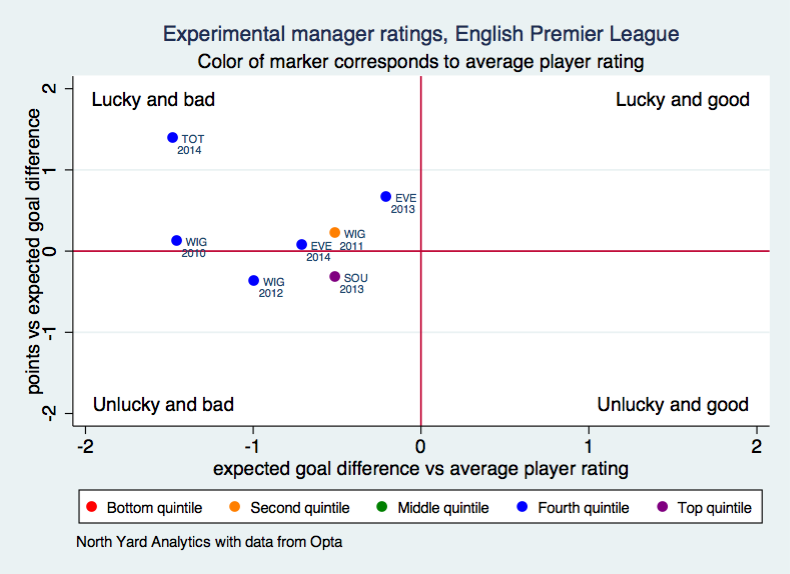

Roberto Martínez and Mauricio Pochettino: (stay away, unless Pochettino has twice been the victim of first-season effects)

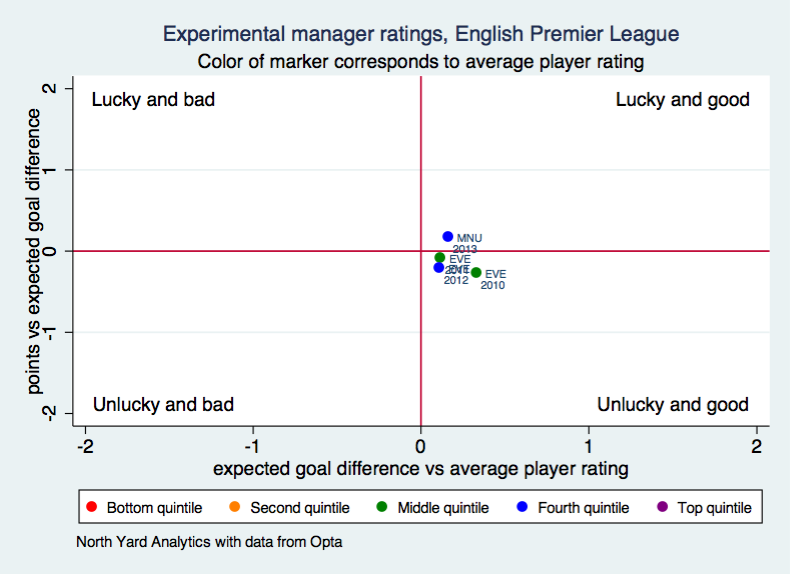

David Moyes: (still Mr. Consistency)

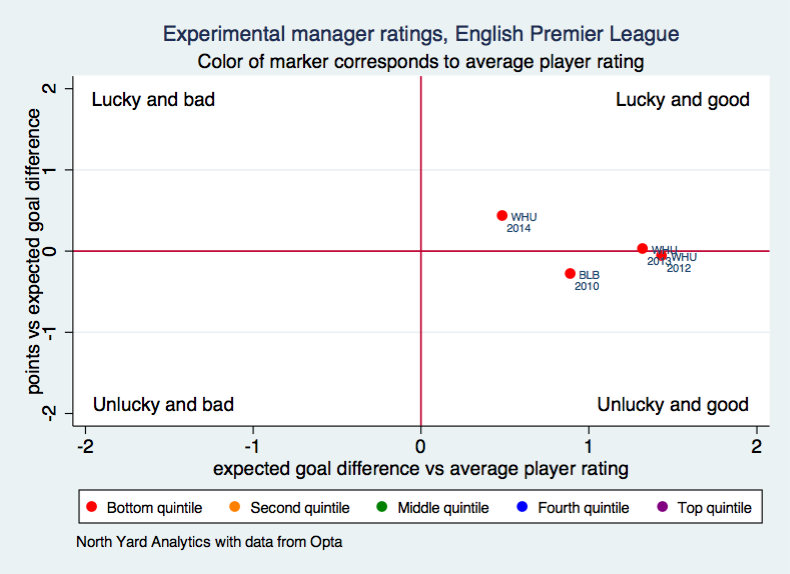

Sam Allardyce, including Blackburn’s full 2010-11 season: (good manager who may be taking a stylistic or recruiting wrong turn at West Ham)

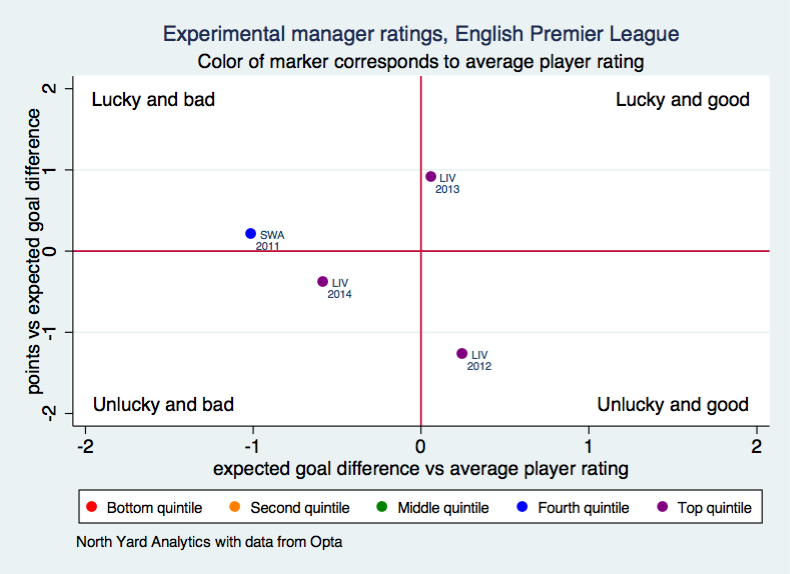

Brendan Rodgers: (lots of good and bad luck, but Liverpool is getting worse the longer he stays there)

In these graphs, the variation in “luck” has been condensed for mid-table teams and enhanced somewhat for teams at the extremes of the table, which is what you’d expect. There’s no change in the horizontal position of the markers, since I haven’t altered the “good” metric.

It’s possible that “luck” is proxying for different styles of play here. Some styles, such as Swansea’s passing approach under recent managers or Stoke under Tony Pulis, may not be the most efficient at converting my measure of player ability into scoring opportunities. But then again, Arsenal have had complete continuity in their manager and to a great degree in their style, yet the club has still had lucky and unlucky seasons by my metric.

For now, I think there are two lessons to be drawn from this analysis: 1) Managerial ability often carries over between clubs, and 2) managers do have lucky seasons. If I ran a club, I’d think twice about hiring a manager who was a habitual underperformer, and I’d also consider sacking a manager who underperformed after more than a year in charge.